移植片の生存は植毛の結果に影響する

移植片の重要性生存

人が生まれた後、毛包は増えません。ドナー部位である後頭部の永久毛包は貴重であり、交換できません。多くの人が毛包のクローン化を期待していますが、成功する時期は不明です。優先事項は、植毛の過程で毛包に生じる外傷を最小限に抑えることです。過去 50 年間、移植された毛髪の実際の生存率と成長率を調べる多くの研究が行われ、次のような結果が報告されています。

• 毛髪は移植の「臓器」と見なされます

• 他の臓器と同様に、体から出た後は慎重に保管する必要があります。そうしないと、死んでしまいます

• 損傷した毛包は、移植後に新しい毛を生成しない場合があります

• 一般的に、移植した毛髪の少なくとも 85% が成長して初めて結果が現れます

• 毛包損傷の原因は、「H 因子」と「X 因子」に分けられます

移植片の生存率とドナー瘢痕

移植片の生存率が高いほど、手術を完了するために必要な量は少なくなります。FUT ドナー瘢痕の幅は切除したストリップの幅に比例するため、生存率が高いほどドナー瘢痕は小さくなります。

移植片の生存率と最終結果

植毛手術の最終結果は、実際に再生する移植片の数によって決まります。Beehner 博士は、移植片の生存率は何よりも手術チームのスキルによって決まるとコメントしました。言い換えれば、手術チームのスキルと経験は、満足のいく結果を得るための最も重要な要素の 1 つです。医師とスタッフは、抽出だけでなく、別の場所に移植した後も成長を維持する方法にも焦点を当てる必要があります。移植片を取り出しても、H 因子 と X 因子 を調べない限り、移植片の成長を保証することはできません。そのため、UR-FUT から FUT-X に進化させる必要があると考えました。

移植片の生存と今後のセッション

毛髪移植は、ドナーの供給が限られているという課題があります。現在まで、毛髪クローニングはまだ利用できません。次の手術のために十分な毛包を確保する最善の方法は、最初のセッションで移植片の無駄を最小限に抑えることです。

手術費用

移植片の生存率が高いほど、手術を完了するために必要な量は少なくなります。ほとんどの植毛センターは「移植した移植片あたり」で請求し、「移植片の生存率あたり」で請求しないため、生存率が高いほど費用は低くなります。そうは言っても、お金で良質なドナー毛包の無駄を買い戻すことはできません。

センター A |

センター B |

|

|---|---|---|

移植片 1 本あたりの費用 (HKD) |

25 |

25 |

| 必要な移植片の数 | 2,400 | 2,400 |

| 総費用(HKD) | 60,000 | 60,000 |

| 切断率 (移植片損傷) | 20% | 2% |

| 損傷移植片の数 | 2,400 X 20% = 480 | 2,400 X 2% = 48 |

| 数完全な移植片の | 2,400 - 480 = 1,920 | 2,400 - 48 = 2,352 |

| 移植片 1 個あたりの実際のコスト (HKD) | 60,000 ÷ 1,920 = 31 | 60,000 ÷ 2,352 = 25.5 |

| 結論: 切断率が高いと移植片 1 個あたりのコストが増加します。 | ||

H 因子と X 因子

ある部位から別の部位に移植しても、良い結果が保証されるわけではありません

移植毛を枯らす原因 - X 因子

「X」は不明を意味します。この用語は、1984 年にオーストラリアのシールド博士によって初めて説明されました。当時、毛髪の成長が減ったことは予想外で、原因も不明でした。初期の頃、この X 因子は、成長しない毛髪全体の 0.5 ~ 1% というごくわずかな割合を占めるに過ぎませんでした。外科手術技術の進歩と標準化により、現在では X 因子が不満足な結果の大部分を占めています。

考えられる X 因子

私たちの意見では、このような「未知の」因子は、実際には手術中および手術後に起こる移植片への生物学的損傷であり、次のようなものがあります:

• H 因子の否定または欠落

• 再灌流虚血性障害

• 移植片の自己拒絶

• 最初の 1 週間の移植片の過熱と脱水

• 不適切なヘアケアや活動

移植片を破壊するもの - H 因子

処置前の H 因子

結果を損なう素因には以下が含まれます:

• 移植部位の血行不良

• 移植予定部位の傷跡

• 喫煙

• 制御不能な糖尿病

処置中の H 因子

処置中に移植片が損傷する:

• 脱水

• 支持組織の過剰な除去

• 寒冷障害

• 毛包の切断

• 保管中の移植片への化学的外傷

• 虚血再灌流障害

処置後の H 因子

移植された卵胞は処置後に損傷を受ける

• 指示に従わない

• 新しい循環を形成できない

• 移植された移植片の物理的外傷

• 感染

移植片生存率を改善する方法

H 因子 1 - 脱水

脱水は、移植片に深刻な損傷を引き起こします。毛包が 5 分以上乾燥すると、細胞の完全性に有害な変化が生じます (Gandelman)。移植片が 10 分以上空気にさらされると、6% 以上が死滅します。 20 分後、生存率は著しく低下します (Kim)

空気暴露時間 (分) |

成長率 |

|---|---|

0 |

96 % |

| 5 | 94 % |

| 10 | 94 % |

| 20 | 83 % |

| 30 | 63 % |

脱水は深刻な移植片損傷を引き起こします。毛包が 5 分以上乾燥すると、細胞の完全性に有害な変化が生じます (Gandelman)。移植片が 10 分以上空気にさらされると、6% 以上が死滅します。20 分を超えると生存率は著しく低下します (Kim)

脱水症状の克服方法

• 手袋をはめた指に移植片を残さないでください

• 2,500 移植片 (5,000 本の毛髪) を超える FUE の使用は避けてください

• インプランターの使用は避けてください

• すべての移植片は、Hypothermosol 溶液または湿らせたガーゼパッドに浸されます

H 因子 2 - 幹細胞の過剰な除去

毛包の周囲の組織を過剰に除去することも、物理的損傷の一種です。毛包の再成長を担う幹細胞は、移植片の周囲の組織にあります。Seager は 1997 年に、Chubby Graft (脂肪が多い) の方が Skinny Graft (脂肪が少ない) よりも生存率が高いと報告しました (Seager)。 2010 年に Beehner は、生存率の違いは、太い移植片では幹細胞が保持されるが、細い移植片では切り取られることにあるとコメントしました

19 か月後の成長率 (%) |

細い移植片 |

太い移植片 |

|---|---|---|

2 毛包単位 |

69.3 % |

88.0 % |

| 1 毛包単位 | 48 % | 98 % |

過剰な幹細胞除去を克服する方法

• 顕微鏡を使用して幹細胞を含む組織を保存します

• FUE で採取する場合は、脂肪組織を残すために必ず大きめのパンチを使用してください

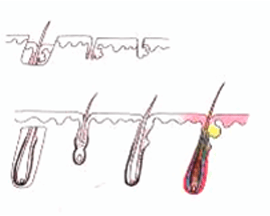

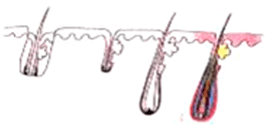

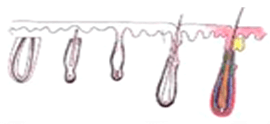

H 因子 3 - 移植片切断

毛包を上部 1/3 で切断 |

||

|

|

上部 1/3 - 0% 成長します |

| 下部 2/3 - 83% が成長します | ||

中央で毛包を切断しました |

||

|

|

上部 1/2 - 40% が成長します |

| 下部 1/2 - 27% が成長します | ||

下部 1/3 で卵胞を切断しました |

||

|

|

上部 2/3 - 65% が成長します |

| 下部 1/3 - 0% が成長します | ||

グラフトを直視および拡大視下で切断することで、グラフト切断を全体の 2% 未満に減らすことができます。

切断を減らす方法 1: オープン テクニック

ストリップ切除では、ブラインド ハーベスティング テクニックが今でもよく使用されています。患者は座って前かがみになります。外科医は後ろに立ち、毛包が見えないようにストリップを切断します。経験豊富な外科医は、既存の毛に沿って刃の角度を調整します。これは白人の短い毛根には有効かもしれませんが、アジア人の長い毛根には有効ではありません。毛包はブラインド ブレードのコースに沿って切断されます。使用する刃の数が増えるほど、生き残るグラフトは少なくなります。

このテクニックは、1998 年にパトムバニッチ博士によって初めて導入されましたが、オープン ドナー ハーベスティングは人気がありません。これは 30 分余分にかかる時間のかかる方法であるため、主に傷跡や最終結果を気にする外科医によって使用されています。

切開を減らす方法 2: 顕微鏡解剖

FUT では、移植に最小の毛包単位が使用されます。毛包の重要な部分は、切断中に簡単に切開される可能性があります。このような移植片は、生き残ったとしても最適な成長が得られません。毛包の完全性を維持する唯一の方法は、拡大鏡で解剖することです。

顕微鏡の使用は、1991 年に Dr Limmer (米国) によって初めて導入されました。しかし、ゴールド スタンダードになるまでに 10 年かかりました。私たちは、その結果が機器とトレーニングへの投資に十分見合うものであると確信しています。私たちは、より鮮明に表示するために、バックライト付きの 10 倍実体顕微鏡を日常的に使用しています。過熱を避けるために、照明にはクール LED ライトを使用しています。移植片は脱水を防ぐために常に湿った状態に保たれています。移植片切断の準備時間を短縮するために、移植片切断のアシスタントを 7 名配置しています。幹細胞を含む組織は、より良好な生存のために保存されます。

H 因子 4 - 再移植の遅延

| 抽出後の期間 (時間) | 成長率 |

|---|---|

2 |

95 |

| 4 | 90 |

| 6 | 86 |

| 8 | 86 |

| 24 | 79 |

表から、4 時間後には移植片の生存率が 90% であることがわかります。つまり、4 時間後には、抽出された移植片の 10% は毛髪を生やしません。ドナーの毛髪は一生のうちに限らているため、これは無駄です。

治療期間を短縮する方法

• FUE 抽出時間を 2 ~ 3 時間に短縮

• 手術時間を短縮するための綿密に計画された手順

• 作業負荷を分担する大規模な外科チーム

• 1 日に 1 件だけ実施して、すべての注意が払われるようにしてください

H 因子 5 - 寒冷障害

これは身体障害の一種です。研究により、凍結した移植片はすべて死滅することが示されています。家庭用冷蔵庫は温度変動がある場合があります。冷蔵庫の温度が低すぎると、0 度以下に下がり、知らないうちに移植片が死んでしまう可能性があります。研究によると、移植片を室温で保管しても 4 度で保管しても、6 時間以内の生存率に大きな違いはありませんでした (Kim)

寒冷障害を克服する方法

• 4 6 時間以内に処置が完了できる場合は、移植片を室温で保管します

• 冷蔵庫で移植片を保管するには、特別な保管液 (Hypothermosol) を使用します

• 移植は 6 時間以内に完了するようにしてください

H 因子 6 - 保管中の移植片の損傷

組織が体から除去されると、細胞は徐々に酸素を使い果たし、最終的には死にます

当社のプロトコル

• ストルゲ溶液として ATP を使用する

• 手術時間を短縮する

循環を改善するための当社のプロトコル

• 患者に喫煙を減らすよう依頼します

• 施術後すぐに低レーザーレベル療法とATPスプレーを使用してください

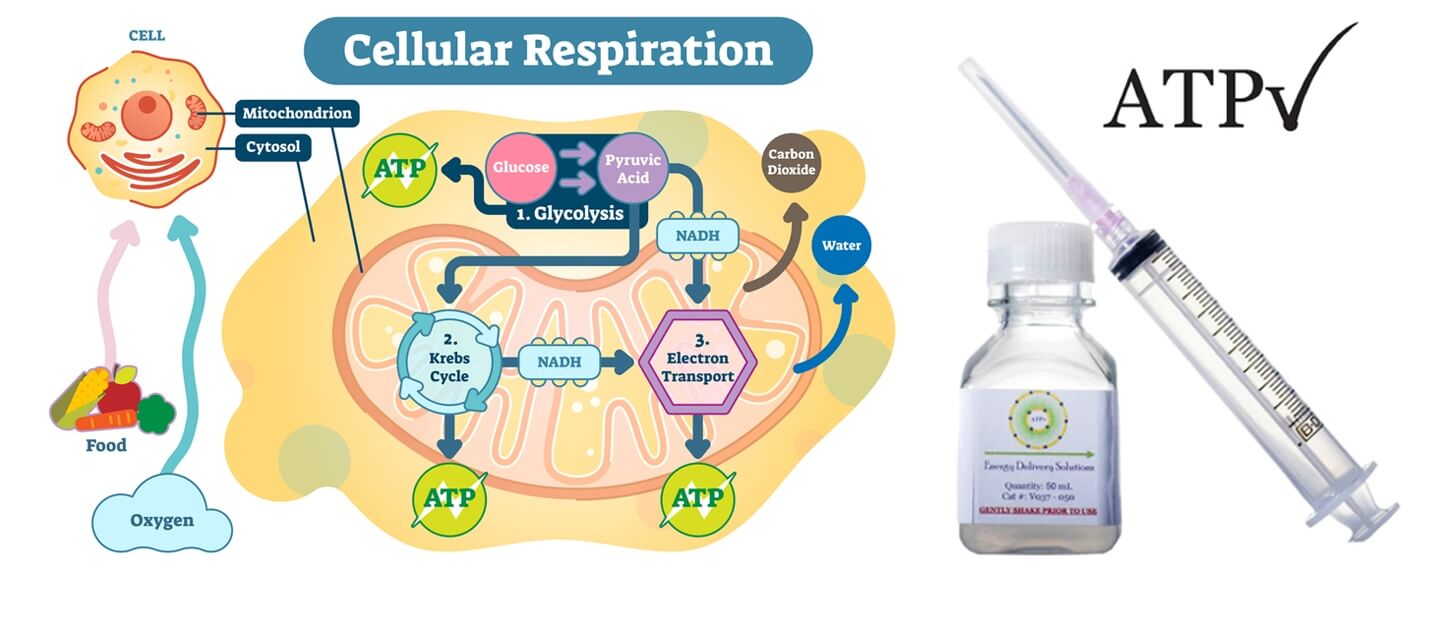

ATPエネルギー供給ソリューション(米国)

ATPとは何ですか?

ATP(アデノシン三リン酸)は、体内のさまざまな重要な細胞反応を触媒するエネルギー分子です。ATPが不足すると、細胞が損傷し、最終的には細胞と組織が死滅する可能性があります。ATPの生成と調節には酸素が必要であるため、酸素が不足した組織はATPが失われ、損傷を受けることがよくあります。このため、ATP は、特に手術による傷の治癒を目指す患者にとって非常に重要になります。

2002 年、ルイビル大学医学部の教授であるウィリアム・エリンガー博士は、ATP をカプセル化して細胞に送達する方法を発見しました。10 年間の研究を経て、最終的な製剤が特定されました - リポソーム ATP。2012 年、エリンガー博士は、手術後の患者、傷の治癒が遅れている患者、および毛髪再生に使用するための ATP を製造する Energy Delivery Solutions を設立しました。

植毛中および植毛後に ATP を使用します

当社の医療顧問である Cooley 博士と Pathomvanich 博士による実験では、植毛手術において、リポソーム ATP を使用すると治癒が早まり、植毛の収量が向上することが示されました。2015 年に、私たちは Energy Delivery Solutions の創設者であるエリンガー博士と会いました。エーリンガー博士とクーリー博士は、どちらも次のことを推奨しています。

1. 移植片を ATP を含む保存液に保管する

2. 最初の 48 時間から最大 5 日間、自宅で移植者の頭皮に ATP 製剤をスプレーする

選ばれた被験者に対する 1 年以上にわたる臨床試験で、非常に印象的な結果が明らかになりました。2016 年 10 月以降、私たちはすべての患者にリポソーム ATP を定期的に提供しています。リポソーム ATP の半減期は非常に短いため、数週間ごとに州から輸入する必要があります。そのメリットは、余分な労力と費用に見合う価値があります。

低出力レーザー療法

植毛は、最初は頭皮に外傷を与える可能性があり、最初の 4 か月間は一時的な脱毛を引き起こす可能性があります (これはショックロスと呼ばれます)。移植部位に腫れが生じる患者もいます。移植されたドナー毛包が新しい環境に適応するのが難しい場合もあります。臨床研究では、レーザーを植毛と併用すると、次のような有益な効果があることが実証されています。

• 抜け毛(ショックロス)を最小限に抑えます

• 手術後の毛包を強化し、生存率を大幅に高めます

• 手術後の腫れ、赤み、炎症を軽減します

細胞エネルギー供給におけるレーザーの効果

レーザー毛髪療法は、細胞内のミトコンドリアを刺激して、アデノシン三リン酸(ATP)の生産を増加させます。ATPは、毛細胞が毛包に成長するために使用するエネルギーの形態です。弱って傷ついた毛包を扱う場合、十分なエネルギー供給が不可欠です。

植毛後の成功率の向上

レーザー毛髪治療装置は、世界中の何千もの植毛センター(Bosley や HairClub など)で使用されています。しかし、安価な発光ダイオード(LED)で作られた手持ち式の装置は、毛包の根元にエネルギーを与えるという点では役に立ちません。当センターでは、植毛後に使用できる、FDA 認可の技術的に高度な装置を現在ご利用いただけます。20 分間の治療で、毛細胞のミトコンドリアを蘇らせることができます。これにより、毛包が強くなり、手術を生き延びる可能性が高まります。これらの余分な「生存」毛髪移植片は、最終的には健康な終毛に成長します。

続きを読む

参考文献

• Aby Mathew. A review of Cellular Bippreservation Consideration During Hair Transplantation. Hair Transplant Forum International, Vol 23 No. 1, January/February 2013

• Baust, J.G. In: J.G. Baust and J.M. Baust, eds. Advances in Biopreservation. CRC Press, 2007; 1-14.

• Snyder, K.K., et al. Biological packaging for the global cell and tissue therapy markets. BioProcessing Journal. 2004(May/June); 1-7.

• Reyes, A.B., J.S. Pendergast, and S. Yamazaki. Mammalian peripheral circadian oscillators are temperature compensated. J Biol Rhythms. 2008; 23:95-98.

• Allen, F.M. Physical and toxic factors in shock. Archives of Surgery. 1939; 38:155-180.

• Bigelow, W.G., W.K. Lindsay, and W.F. Greenwood. Hypothermia: its possible role in cardiac surgery: an investigation of factors governing survival in dogs at low body temperature. Annals of Surgery. 1950; 132:849-866.

• Swan, H., et al. Hypothermia in surgery: analysis of 100 clinical cases. Annals of Surgery. 1955; 142:382-400.

• Collins, G.M., M. Bravo-Shugarman, and Pl. Terasaki. Kidney preservation for transplantation: initial perfusion and 30 hours ice storage. Lancet. 1969; 2:1219.

• Taylor, M.J., et al. A new solution for life without blood: asanguineous low flow perfusion of a whole-body perfusate during 3 hours of cardiac arrest and profound hypothermia. Circulation. 1995; 91:431-444.

• Van Buskirk, R.G., et al. Assessment of hypothermic storage of normal human epidermal keratinocytes (NHEK) using Alamar Blue. In Vitro Toxicology. 1996; 9:297-303.

• Mathew, A.J., J.G. Baust, and R.G. Van Buskirk. Optimization of HypoThermosol for the hypothermic storage of cardiac cells—addition of EDTA. In Vitro Toxicology. 1997; 10(4):407-415.

• Mathew, A.J., et al. Vitamin E and EDTA improve the efficacy of HypoThermosol—implication of apoptosis. In Vitro Toxicology. 1999; 12(3):163-172.

• Dahdah, N.S., et al. Effects of HypoThermosol, an experimental acellular solution for tissue preservation and cardiopulmonary bypass, on isolated newborn lamb coronary vessels subjected to ultraprofound hypothermia and anoxia. Cryobiology. 1999; 39:58-68.

• Mathew, A.J., J.G. Baust, and R.G. Van Buskirk. Improved hypothermic preservation of human renal cells through suppression of both apoptosis and necrosis. Cell Preservation Technology. 2003; 1:239-254.

• Baust, J.M., et al. Transplantation diagnostics: utilization of protein microarray analysis to determine kidney status and transplantation efficacy. Cell Preservation Technology. 2004; 2(2):81.

• Mathew, A.J., et al. Cell preservation in reparative and regenerative medicine: evolution of individualized solution composition. Tissue Engineering. 2004; 10:1662-1671.

• Snyder, K.K., et al. Biological packaging for the global cell and tissue therapy markets. BioProcessing Journal. 2004; 3(3):39.

• Van Buskirk, R.G., et al. Hypothermic storage and cryopreservation: the issues of successful short-term and long term preservation of cells and tissues. BioProcess Int’l. 2004; 2(10):42.

• Baust, J.M. Advances in media for cryopreservation and storage. BioProcess International. 2005; 3:46-56.

• Snyder, K.K., et al. Enhanced hypothermic storage of neonatal cardiomyocytes. Cell Preservation Technology. 2005; 3(1):61-74.

• Mathew, A.J. I’m losing cell viability and function at different points in my process, and I don’t know why! BioProcess Int’l. 2010; 8(6) 54-7.

• Ikonomovic, M., et al. Ultraprofound cerebral hypothermia and blood substitution with an acellular synthetic solution maintains neuronal viability in rat hippocampus. CryoLetters. 2001; 22:19-26.

• Lodish, H.F., et al. Transport across cell membranes. In: S. Tenney, ed. Molecular Cell Biology. 4th Edition. New York: W.H. Freeman, 2000; 590-591.

• MacKnight, A.D.C., and A. Leaf. Regulation of cellular volume. Physiology Review. 1977; 57:510.

• Martin, D.R., et al. Primary cause of unsuccessful liver and heart preservation: cold sensitivity of the ATPase system. Annals of Surgery. 1972; 175:11.

• Boutilier, R.G. Mechanisms of cell survival in hypoxia and hypothermia. J of Experimental Biology. 2001; 204:3171-3181.

• Toledo-Pereyra, L.H., A.J. Paez-Rollys, and J.M. PalmaVargas. Science of organ preservation. In: L.H. ToledoPereyra, ed. Organ Procurement and Preservation for Transplantation. Landes Bioscience, 1997; 1-16.

• Rehncrona, S., B.K. Siesjo, and D.S. Smith. Reversible ischemia of the brain: biochemical factors influencing restitution. ActaPhysioliogy Scandinavia. 1979; Suppl 492:135.

• Cotterill, P. ISHRS survey majority using chilled saline. W. Reed Personal communication, December 2012. Reed, W. Personal communication, December 2012.

• Perez-Meza, D., M. Leavitt, and M. Mayer. The growth factors. Part 1: clinical and histological evaluation of the wound healing and revascularization of the hair graft after hair transplant surgery. Hair Transplant Forum Int’l. 2007; 17(5):173.

• Perez-Meza D. Wound healing and revascularization of the hair transplant graft: role of the growth factors. In: W. Unger and R. Shapiro, eds. Hair Transplantation, 4th Ed. Marcel Dekker, New York, 2004; 287-294.

• Cooley, J. Ischemia-reperfusion injury and graft storage solutions. Hair Transplant Forum Int’l. 2004; 14(4):121,127,130.

• Parsley, W.M., and D. Perez-Meza. Review of factors affecting the growth and survival of follicular grafts. J Cutan Aesthet Surg. 2010; 3(2):69-75.

• Limmer, R. Micrograft survival. In: D. Stough, ed. Hair Replacement. Mosby Press, 1996; 147-149.

• Kim, J.C., and S. Hwang. The effects of dehydration, preservation temperature and time, and hydrogen peroxide on hair grafts. In: W.P. Unger and R. Shapiro, eds. Hair Transplantation, 4th Ed. New York: Marcel Dekker, 2004; 285-286.

• Hwang, S.J., et al. The effects of dehydration, preservation temperature and time on the hair grafts. Annals of Dermatology. 2002; 14:149-152. 37. Krugluger, W., et al. Enhancement of in vitro hair shaft

elongation in follicles stored in buffers that prevent follicle cell apoptosis. Dermatol Surg. 2004; 30:1-5.

• Krugluger, W., et al. New storage buffers for micrografts enhance graft survival and clinical outcome in hair restoration surgery. Hair Transplant Forum Int’l. 2003; 13(3):333-334.

• Van Buskirk, R.G., et al. Navigating the post-preservation viability fog: assay standardization for cell and tissue therapy applications. Genetic Engineering News. 2006; 26(19):38-39.

• Van Buskirk, R. Viability and functional assays used to assess preservation efficacy: the multiple endpoint/tier approach. In: J.G. Baust and J.M. Baust, eds. Advances in Biopreservation. CRC Press-Taylor and Francis Publishing: New York, 2006.

• Belzer, F., and J. Southard. Principles of solid-organ preservation by cold storage. Transplantation. 1988; 45(4):673-676.

• Taylor, M.J. The role of pH and buffer capacity in the recovery of function of smooth muscle cooled to –13°C in unfrozen media. Cryobiology. 1982; 19:585-60.

• Taylor, M.J., and Y. Pignat. Practical acid dissociation constants, temperature coefficients and buffer capacities for some biological buffers in solutions containing dimethyl sulfoxide between 25 and –12°C. Cryobiology. 1982; 19:99-109.

• Fujita, J. Cold shock response in mammalian cells. J Mol Microbiol Biotechnol. 1999; 1(2):243-255.

• Plesnila, N., et al. Effect of hypothermia on the volume of rat glial cells. Journal of Physiology. 2000; 523.1:155-162.

• Tseng, Y-C, et al. Exploring uncoupling proteins and antioxidant mechanisms under acute cold exposure in brains of fish. PLoS ONE. 2011; 6(3):1-15.

• Corwin, W.L., et al. The unfolded protein response in human corneal endothelial cells following hypothermic storage: Implications of a novel stress pathway. Cryobiology. 2011; 63(1):46-55.

• Baust, J.M. Overview of hypothermic storage. Hair Transplant Forum Int’l. 2006; 16(2):53.

• Cosentino, L.M., et al. Preliminary report: evaluation of storage conditions and cryococktails during peripheral blood mononuclear cell cryopreservation. Cell Preservation Technology. 2007; 5:189-204.

• Baust, J.M., R.G. Van Buskirk, and J.G. Baust. Cell viability improves following inhibition of cryopreservation-induced apoptosis. In Vitro Cell and Developmental Biology. 2000; 36:262.

• Baust, J.M., et al. A molecular basis of cryopreservation failure and its modulation to improve cell survival. Cell Transplantation. 2001; 10:561.

• Baust, J.M., R.G. Van Buskirk, and J.G. Baust. Gene activation of the apoptotic caspase cascade following cryogenic storage. Cell Preservation Technology. 2002; 1:63.

• Baust, J.M. Molecular mechanisms of cellular demise associated with cryopreservation failure. Cell Preservation Technology. 2002; 1:17.

• Anderson, R.V., M.G. Siegman, and R.S. Balaban. Hyperglycemia increases cerebral intracellular acidosis during circulatory arrest. Annals of Thoracic Surgery. 1992; 54:1126-1130.

• Ely, S.W., and R.M. Berne. Protective effects of adenosine in myocardial ischemia. Circulation. 1992; 85:893-904.

• Bessems, M., et al. Preservation of rat livers by cold storage: a comparison between the University of Wisconsin solution and HypoThermosol. Ann Transplant. 2004; 9(2):35-37.

• Povsic, T., et al. A double-blind, randomized, controlled, multicenter study to assess the safety and cardiovascular effects of skeletal myoblast implantation by catheter delivery in patients with chronic heart failure after myocardial infarction. American Heart Journal. 2011; 162(4):654-662.

• Powell, R., et al. Interim analysis results from the RESTORE-CLI, a randomized, double-blind multicenter phase II trial comparing expanded autologous bone marrow-derived tissue repair cells and placebo in patients with critical limb ischemia. J of Vasc Surg.2011; 54(4):1032-1041.

• Ginis, I., B. Grinblat, and M. Shirvan. Evaluation of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells after cryopreservation and hypothermic storage in clinically safe medium. Tissue Engineering Part C Methods. 2012; 18(6):453-463.

• Lowe, N.J., P.L. Lowe, and J. St Clair Roberts. A phase IIa open-label dose-escalation pilot study using allogeneic human dermal fibroblasts for nasolabial folds. Dermatol Surg. 2010;

36(10):1578-1585.

• Raposio, E., et al. Effects of cooling micrografts in hair transplantation surgery. Dermatol Surg. 1999; 25:705-707.

• Jiange, Q., et al. How long can hair follicle units be preserved

at 0 and 4°C for delayed transplant? Dermatol Surg. 2005; 31:23-26.

• Kurata, S., et al. Viability of isolated single hair follicles preserved at 4°C. Dermatol Surg. 1999; 25:26-29.

• Beehner, M.L. Notes from the Editor Emeritus. Hair Transplant Forum Int’l. 2005; 15(6):193-195.

• Cooley, J.E. Successful extended storage of hair follicles using hypothermic media with liposomal ATP. Translational Regenerative Medicine Forum. 2010.

• Beehner, M.L. 96-hour study of FU graft “out-of-body” survival comparing saline to HypoThermosol/ATP solution. Hair Transplant Forum Int’l. 2011; 21(2):1, 37.

• Ehringer, W.D. New horizons in storage solutions and additive agents in organ transplantation. Norwood Lecture, ISHRS 2011 Annual Scientific Meeting.